As U.S. schools and classrooms become increasingly multicultural, the diversity of teachers is not keeping pace. In general, 53% of students in the US were nonwhite in 2020 (KidsData.org, 2020). The percentage of white children is predicted to decrease from 48% to 44% by 2029 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2020). This compares to only 20% of teachers being nonwhite in the US (Geiger, 2018, Aug. 27). Because teachers and students are not distributed evenly across states, regions, and schools, diversity varies considerably. For example, more nonwhite teachers work in schools that are over 90% nonwhite, while white teachers make up 98% of those in predominantly white schools.

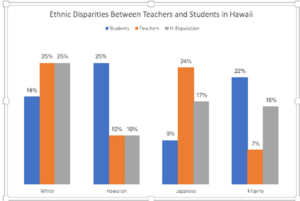

Hawaii, even with its unique ethnic makeup, shows significant ethnic disparities between teachers and students (State of Hawaii, 2019). In the 2017-18 school year, almost 25% of students were Native Hawaiian, 22% were Filipino American, 19% white and 9% Japanese American (State of Hawaii, 2019). This composition was different than that of teachers who were largely white (25%) or Japanese American (23%). Ten percent of teachers were Native Hawaiian and 7% Filipino American. See Figure 1 for comparisons among the four major ethnicities in the State for students, teachers and the State population for these four largest groups.

Differences can be exacerbated depending on geographic location in the state. For example, 50% to 60% of teachers in Hawaii are recruited from outside of the State, who often are white, and may stay for only a few years, causing excessive turnover in schools with the most needs (Richards, 2019). These teachers are often newer to the field and bring fewer skills and experiences to bear in their classrooms. In addition, teachers in disciplines with the most job openings, such as special education and STEM fields, are more likely to be hired on an emergency basis with less education and skills than licensed teachers (Richards, 2019).

These differences can affect students’ and families’ engagement in school, teacher longevity in the job, and student achievement (Murray, 2009; Suarez-Orozco et al., 2009). It is important that educators learn and understand how to work with students and families who are different from themselves.

Many terms are used to designate and discuss the skills and dispositions we need to relate to people who are different from ourselves. These include cultural responsibility, cultural responsiveness, cultural sensitivity, cultural competence, and cultural intelligence. Each of these means something slightly different. Cultural responsibility entails our protecting and supporting our own and others’ cultural history and activity. Cultural responsiveness is a pedagogy that recognizes the importance of including students’ cultural references in all aspects of learning (Ladson-Billings, 1994). Cultural sensitivity involves being aware of cultural differences and similarities without evaluating these as good or bad. Cultural competence entails possessing knowledge and skills required to manage cross-cultural relationships effectively. Cultural intelligence (Ang et al., 2020) builds on the work of Robert Sternberg (1999) around the theory of multiple loci of intelligence, and includes four categories of drive, knowledge, strategy and action.

Most materials and research about cultural competence mirror the four factors of cultural intelligence by urging people to not only know information about other cultures (knowledge), but to be confident in how to engage with others (strategy), to be willing to learn more (drive) (Brislin, 1993), and finally to act (action). In other words, it is not enough to have knowledge about other cultures; if you are not willing to engage and develop relationships with others, you will not be successful.

A way to frame discussion and thought about this issue of diversity is the idea of implicit bias and its contrasting factor of social justice. Implicit bias is, “the stereotypes and attitudes that occur unconsciously and may or may not reflect our actual attitudes” (Gullo et al., 2019, p. 19). Each of us grew up in different circumstances- we are shaped by our parents and family members, neighborhoods, socioeconomic class and experiences, cultures, genders, sexual orientations, and other perceptions of ourselves and others that we learned. The ideas that govern our behaviors and attitudes are often unconscious and can compete with our more overt ideas about social justice and equity.

Some researchers believe that, although we all have implicit biases, they do not affect behavior enough to cause concern (Arkes & Tetlock, 2004). Others believe that these biases need to be recognized and managed in order to reduce discriminatory behavior patterns that have been observed in police enforcement, education and other realms (Gullo & Beacham, 2020). Harvard University hosts a website where anyone can test for implicit biases at: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html. On this site, you can take tests for biases regarding weight, gender, weapons, Asian Americans, Native Americans, transgender, age, skin tone, religion, presidents, disability, sexuality, Arab/Muslims, and race (Black/white). Managing implicit biases entails becoming aware of it, recognizing its potential effects, and countering those effects through action. For example, if you discover an implicit bias against a certain group, take action to engage with people from that group and be aware how your bias could affect your actions. It is equally important to recognize injustice in others’ actions and in the structures of organizations and society and work to promote justice.

Gullo and Beacham (2020) identified social injustice not as “outright violence, blatant bigotry, and/or unjust laws, but rather a sub-optimal worldview that leads to injustice” (p. 2). This worldview is characterized by materialism, competition and individualism as opposed to spiritualism, communalism and oneness with nature. They developed a framework for educational leaders to decrease implicit bias and increase social justice in schools. The framework includes decision-making supports, inter-group contact, information building, and mindfulness about relationships, flexibility and morality.

Social justice in education includes three elements: “fair distribution of educational resources, justice in terms of curriculum and pedagogical matters, and the matter of power in terms of who has power and who should be empowered” (Gullo et al., 2019, p. 3). Much has happened in education to address issues of injustice. One curricular example is the recognition in many community colleges that developmental classes can trap students who can never satisfy the math and English requirements and drop out. The development of integrated credit-bearing classes and other strategies that help students to succeed while addressing their developmental concerns has, in many cases, transformed this level of education (Attewell et al., 2006; Boatman et al., 2020). But, there is much more to accomplish to achieve equity and social justice.

Colonialism is another aspect of injustice that can be easily overlooked (Lam, 2019; Seawright, 2014). The United States, Spain, France and Great Britain are only a few of the colonial powers whose effects have pervaded education around the world. Becoming aware of the effects of imperial aggressions and recognizing how settler colonialism in the US affects perceptions of place, culture, people and behaviors can help to determine how we teach in order to promote equity and justice. These ideas are complex, and indigenous practices need to be upheld, centered and celebrated in educational contexts rather than merely included, yet subjugated in the curriculum. Indigenous teachers are nation builders; indigenous practices are alive and current—not simply part of history (Kulago, 2019). We are beginning these things in Hawai’i, but much more needs to be done to center the culture of these islands.

References

Ang, S., Ng, K., & Rockstuhl, T. (2020). Cultural Intelligence. In R. Sternberg (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence (pp. 820-845). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108770422.035

Arkes, H. R., & Tetlock, P. E. (2004). Attributions of implicit prejudice, or “Would Jesse Jackson ‘fail’ the Implicit Association Test?”. Psychological Inquiry, 15(4), 257-278.

Attewell, P. A., Lavin, D. E., Domina, T., & Levey, T. (2006). New evidence on college remediation. Journal of Higher Education, 77(5), 886-924.

Boatman, A., Cerna, O., Reiman, K., Diamond, J., Visher, M. G., & Rutschow, E. Z. (2020). Building a new “bridge” to math: A study of a transition program serving students with low math skills at a community college(ED604250). MDRC. https://eric.ed.gov/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=ED604250

Brislin, R. (1993). Understanding culture’s influence on behavior. Harcourt Brace.

Geiger, A. W. (2018, Aug. 27). American’s public school teachers are far less racially and ethnically diverse than their students. Fact Tank. https://pewrsr.ch/2P2Wgf6

Gullo, G., & Beacham, F. (2020). Framing implicit bias reduction in social justice leadership. Educational leadership and policy studies, 3(3, spec iss 3).

Gullo, G., Capatosto, K., & Staats, C. (2019). Implicit Bias in Schools. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351019903

KidsData.org. (2020). Public School Enrollment, by Race/Ethnicity KidsData.org. https://www.kidsdata.org/topic/36/school-enrollment-race/table – fmt=451&loc=1&tf=110&ch=7,11,726,85,10,72,9,73&sortColumnId=0&sortType=asc

Kulago, H. A. (2019). In the business of futurity: Indigenous teacher education & settler colonialism. Equity and Excellence in Education, 52(2-3), 239-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2019.1672592

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The dreamkeepers. Jossey-Bass Publishing Co.

Lam, K. D. (2019). Critical ethnic studies in education: Revisiting colonialism, genocide, and US Imperialism—An introduction. Equity and Excellence in Education, 52(n2-3), 216-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2019.1672595

Murray, C. (2009). Parent and teacher relationships as predictors of school engagement and functioning among low-income urban youth. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29(3), 376-404. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431608322940

National Center for Education Statistics. (2020). Racial/ethnic enrollment in public schools. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved November 19, 2020 from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cge.asp

Richards, E. (2019, April 5). “Living with 2 roommates in a dump’: Hawaii is too expensive to be paradise for teachers.USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2019/04/05/apartments-real-estate-hawaii-teaching-jobs/3357914002/

Seawright, G. (2014). Settler traditions of place: Making explicit the epistemological legacy of white supremacy and settler colonialism for place-based education. Educational Studies, 50, 554-572. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2014.965938

State of Hawaii. (2019). State of Hawaii Data Book. http://dbedt.hawaii.gov/economic/databook/2019-individual/_03/

Sternberg, R. J. (1999). A triarchic approach to the understanding and assessment of intelligence in multicultural populations. Journal of School Psychology, 37(2), 145-159.

Suarez-Orozco, C., Pimental, A., & Martin, M. E. (2009). The significance of relationships: Academic engagement and achievement among newcomer immigrant youth. Teachers College Record, 111(3), 712-749.