When parents and families do not participate in schools, teachers often assume parents do not value their children’s school work1. However, researchers have found that, when asked, many families indicate that they care passionately about their children’s education2.

Instead of assuming that families do not care, educators can examine their own biases. Research suggests that many teachers often do not have high expectations for students and families, especially those who do not speak English well. These and other biases, such as those toward poverty, homelessness, or races other than their own can be subtle and hidden from educators themselves.

Another major obstacle to developing educational partnerships, families and schools may have different views about the roles that teachers, families, students, and the school play in the educational process.

For example, Latino families feel that they are responsible for nurturing and educating their children at home, not at school, to the point where in many Latin American countries it is considered rude for a parent or family member to intrude into the life of the school, just as it is rude for schools to intercede in the moral and ethical education of the children at home. Minority and low income parents, even those coming from the same country, are a diverse group in themselves, so one should not overgeneralize cultural trends. However, it can be helpful for teachers to learn about immigrant cultures at the same time valuing parents’ individual personalities and differences within a particular culture.

Another difference is how much information families and teachers directly exchange with each other. For example, in China, parents and families get plenty of information about their children’s education indirectly through children’s completed textbooks, daily homework assignments, and the scores of frequent tests. Parents of high school students in Taiwan are required to sign the homework booklet before the child returns it to the school.

Family engagement has traditionally been defined as parents participating in a scripted role to be performed1. This role is a social construct driven by mainstream white, middle-class values2. For example, typical ways of parent involvement include participation in parent teacher organizations and in fundraising activities. To be involved in these socially sanctioned ways, parents and family members must be aware of such scripts and they also have to be willing and capable of performing those functions.

However, these traditional involvement roles are often outside the cultural repertoires of parents who do not belong to the white, middle-class group, and thus they end up not being involved in schools in expected ways3. This often leads to parents been seen as uninvolved, unconcerned, and maybe even uncaring4.

Contrary to this view, many researchers have pointed out that minority, immigrant, and low socioeconomic families do care about their children and are involved in their education in many ways, even though many of those venues are not recognized and sanctioned by schools5.

For example, researchers have found:

- Micronesian families do not view education as an end in itself. Families value education and consider it a venue for better jobs and livelihoods, and some go to the extent of making significant sacrifices for the education of their children, like sending them away to relatives who live in areas where parents perceive the schools to be of better quality. However, some differences in the views of education, along with linguistic and cultural barriers, pose a challenge. For example, while education is compulsory to age 14 in the Federated States of Micronesia, school attendance is not strictly enforced. Students are not used to participating in instructional approaches such as problem-solving, independent learning, and shared decision-making. However, they are comfortable working with peers and “borrowing” from a friend, practices that are not always acceptable in American schools (Heine, 2003).

- Family obligations are essential in Micronesian culture and include a broad range of activities. Because of their immigration status and being away from home, many of these practices are actually strengthened and Micronesian students and their families show powerful allegiances to their cultural obligations and their home islands. These bonds are important and may lead to these families having less commitment to outside influences, such as school (Ratliffe, 2010).

- Spanish-speaking parents emphasize good morals by communicating with the child, knowing the child’s friends, providing encouragement, establishing trust with the child, and teaching good values. Academic involvement is less frequent and includes asking about and signing homework, attending conferences, and going to the library (Zarate, 2007).

- For many Mexican families in the US near the Mexican/USA border, parents strongly favor their children graduating from high school as a way to empower them to provide economic support to the family. However, while education is seen as important, it doesn’t always come first. Some families may feel that people with “too much education” are not managing the practical matters of daily life. Children are expected to work after school to support the family rather than moving on to study in college (Valdés, 1996).

- For Taiwanese families in Vancouver, parents were dissatisfied with Canadian schools’ common holistic learner-centered approaches and with the long periods of two to three years their children spent in non-credit ESL classes (without clear criteria for advancement). Parents were anxious to mainstream their children as a way to enhance ESL learning and to allow their children to learn content-area material. The parents also preferred greater use of testing, more intensive homework, and teachers as disciplinarians (Salzberg, 1998).

- Chinese American parents are more likely than European parents to spend time helping their children with schoolwork in their homes, but they participate less in school activities than European parents (Kao, 1998).

- Chinese families in the UK value education highly and believe in the English/UK model of education but would like more homework and a stricter regime in schools (Ghuman & Wong, 1989).

In addition, there is evidence that some teachers may actually discourage family participation in school curricular activities6. Often, these teachers believe that families’ first-language interaction with their children interferes with second-language learning. This belief has been refuted by many scholars7, but some teachers still strongly hold such a belief and advise families to not speak their native language at home8. When families attend to teachers’ suggestions and stop speaking their first language at home, they do a disservice to the children since this may actually hamper their efforts to learn English. In addition, it may limit the input teachers receive from families and jeopardize students’ cultural and linguistic identities9. Supporting students’ use of and development of their native language is a strategy that allows children to continue to develop their first language, to be stronger and quicker in acquiring their second language, and to avoid the loss of important links to family and community10.

Asking families not to speak their first language at home might be detrimental in other ways as well. By forcing families to speak in English, the children are exposed to an “imperfect variety of English” 11. While there is some truth in the notion that families who have limited English might be less able to elaborate and extend the language and thinking processes of their children, it is important not to disparage families’ communication efforts in English and to recognize that English has many valid varieties. Complaints about people who do not speak “proper” English have been around for a long time12. This is known as the “standard language ideology”13, which can be understood as a bias toward an abstract idealized spoken language modeled on the written and the spoken language of the upper middle class. Teachers should avoid using this deficit view and instead focus on the added benefits of maintaining the first language and of being bilingual.

1. Lopez, 2001

2. Crozier, 2001; Guo, 2006; Lareau, 1987, 1989; Lareau & Benson, 1984; Lightfoot, 2004

3. Delgado-Gaitán, 1990; Valdés, 1996

4. Lightfoot, 1978

5. Guo, 2012

6. Cummins, 1986

7. Coelho, 2004; Cummins, 2005

8. Guo, 2006

9. Scarcella, 1990

10. Wong-Fillmore, 1991

11. Scarcella, 1990, p. 167

12. Milroy & Milroy, 1985

13. Lippi-Green, 1997

Activities

What are your attitudes toward diverse families and students?

Read, complete a survey, and consider the hidden misunderstandings you may have about a cultural group or group of students and their families and how these may affect your relationships with them.

To learn more about your own underlying attitudes toward diverse families and students, you will read an article, take a test and reflect on your thinking and actions.

1. Read the article “Test Yourself for Hidden Bias” at http://www.tolerance.org/activity/test-yourself-hidden-bias

Do you think you have any (hidden) attitudes or biases for any particular groups (e.g., based on racial, religious, or sexual orientation)? Do you feel more or less comfortable working with certain groups of students or families?

2. Go to https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/ and take a Hidden Bias Test (Implicit Association Test; IAT).

3. What did you discover by taking one or several of the IATs? Do you agree with the findings? Reflect on how you interact and engage with the students, colleagues, and parents of groups that you might have hidden biases toward.

4. Consider ways that you can further explore and confront your feelings (hidden biases) so as to prevent you from having fruitful relationships with your students and their families.

InTASC Model Core Teaching Standards

Standard #2: Learning Differences

2(m) The teacher respects learners as individuals with differing personal and family backgrounds and various skills, abilities, perspectives, talents, and interests.

2(o) The teacher values diverse languages and dialects and seeks to integrate them into his/her instructional practice to engage students in learning.

Standard #3: Learning Environments

3(a) The teacher collaborates with learners, families, and colleagues to build a safe, positive learning climate of openness, mutual respect, support, and inquiry.

3(c) The teacher collaborates with learners and colleagues to develop shared values and expectations for respectful interactions, rigorous academic discussions, and individual and group responsibility for quality work.

3(f) The teacher communicates verbally and nonverbally in ways that demonstrate respect for and responsiveness to the cultural backgrounds and differing perspectives learners bring to the learning environment.

Standard #7: Planning for Instruction

7(n) The teacher respects learners’ diverse strengths and needs and is committed to using this information to plan effective instruction.

Standard #9: Professional Learning and Ethical Practice

9(e) The teacher reflects on his/her personal biases and accesses resources to deepen his/her own understanding of cultural, ethnic, gender, and learning differences to build stronger relationships and create more relevant learning experiences.

9(i) The teacher understands how personal identity, worldview, and prior experience affect perceptions and expectations, and recognizes how they may bias behaviors and interactions with others.

9(j) The teacher understands laws related to learners’ rights and teacher responsibilities (e.g., for educational equity, appropriate education for learners with disabilities, confidentiality, privacy, appropriate treatment of learners, reporting in situations related to possible child abuse).

9(m) The teacher is committed to deepening understanding of his/her own frames of reference (e.g., culture, gender, language, abilities, ways of knowing), the potential biases in these frames, and their impact on expectations for and relationships with learners and their families.

Standard #10: Leadership and Collaboration

10(q) The teacher respects families’ beliefs, norms, and expectations and seeks to work collaboratively with learners and families in setting and meeting challenging goals.

1. “Test Yourself for Hidden Bias” article at http://www.tolerance.org/activity/test-yourself-hidden-bias

2. Hidden Bias Test (Implicit Association Test; IAT) at https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/

3. Cooper, C.W. (2003). The detrimental impact of teacher bias. Teacher Education Quarterly, 101-112. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ852360.pdf

Is there any type of institutional racism at your classroom or school?

Examine the implicit and explicit dialog occurring at your school. Consider how institutional racism, while openly opposed, may still take place in some aspects of the functioning of your classroom or your school. What can you do to address it? Choose a couple of strategies to remedy covert racism and try them in your practice.

In this activity, you will examine the implicit and explicit dialog occurring at your school. You will consider how institutional racism, while openly opposed, may take place in some aspects of the functioning of your classroom or your school. You will think about possible ways to address it.

1. Read the article “Racism in Schools: Unintentional But No Less Damaging” at http://www.psmag.com/culture-society/racism-in-schools-unintentional-3821/ and/or watch a short video and listen to Jim Scheurich, a university professor in Educational Administration at the University of Texas at Austin, speak of some examples of institutional racism, which you can find at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y1z-b7gGNNc

2. Reflect on the article and/or video and, if possible, discuss it with a colleague(s). Do you see any signs of systematic racism at your school? Ideally, you should talk to several people to get various perspectives and obtain a strong sense of how systematic racism is perceived at the school, how much it is recognized, and where it exists. Think about the three Rs mentioned in the article. Do you see them as an integral part of your classroom and school culture?

3. Watch the documentary “Not in Our Town: Light in the Darkness.” After watching the movie, discuss it with a friend, colleague, or other trusted educator. How do you feel about what occurred in this small community? Do you see any similar signs of growing racism (or existing but unrecognized racism) in your community? What do you think you can do about it? Share your ideas with others in your educational community.

4. Read the article “Strategies and Activities for Reducing Racial Prejudice and Racism” at http://ctb.ku.edu/en/tablecontents/sub_section_main_1173.aspx and answer the questions: 1) What is racial prejudice and racism? 2) Why is it important to reduce racial prejudice and racism? 3) How can you reduce racial prejudice and racism?

5. Assess your school, community, and other environments for signs of institutional racism. Talk about it with others and make an action plan based on what you found.

InTASC Model Core Teaching Standards

Standard #2: Learning Differences

2(m) The teacher respects learners as individuals with differing personal and family backgrounds and various skills, abilities, perspectives, talents, and interests.

2(n) The teacher makes learners feel valued and helps them learn to value each other.

2(o) The teacher values diverse languages and dialects and seeks to integrate them into his/her instructional practice to engage students in learning.

Standard #3: Learning Environments

3(n) The teacher is committed to working with learners, colleagues, families, and communities to establish positive and supportive learning environments.

Standard #9: Professional Learning and Ethical Practice

9(i) The teacher understands how personal identity, worldview, and prior experience affect perceptions and expectations, and recognizes how they may bias behaviors and interactions with others.

Standard #10: Leadership and Collaboration

10(b) The teacher works with other school professionals to plan and jointly facilitate learning on how to meet diverse needs of learners.

10(c) The teacher engages collaboratively in the school-wide effort to build a shared vision and supportive culture, identify common goals, and monitor and evaluate progress toward those goals.

10(j) The teacher advocates to meet the needs of learners, to strengthen the learning environment, and to enact system change.

10(k) The teacher takes on leadership roles at the school, district, state, and/or national level and advocates for learners, the school, the community, and the profession.

10(l) The teacher understands schools as organizations within a historical, cultural, political, and social context and knows how to work with others across the system to support learners.

10(m) The teacher understands that alignment of family, school, and community spheres of influence enhances student learning and that discontinuity in these spheres of influence interferes with learning.

1. “Racism in Schools: Unintentional But No Less Damaging” article at http://www.psmag.com/culture-society/racism-in-schools-unintentional-3821/

2. A short video about institutional racism by Jim Scheurich, an associate professor in educational administration and director of Public School Executive Leadership Programs at the University of Texas at Austin: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y1z-b7gGNNc

3. The movie documentary “Not in Our Town: Light in the Darkness.” http://video.pbs.org/program/not-our-town-light-darkness/

4. Research detects bias in classroom observations by Education Week. http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2014/05/13/32observe.h33.html

5. Is my school racist? http://www.tolerance.org/magazine/number-45-fall-2013/is-my-school-racist

Identify and address gaps in teacher-family views of education

Read about what parents say about the role of education; learn about mismatches between teachers’ and parents’ cultural values, views on the role of parents, and views of the role of teachers; and survey the families you work with to find out what their views are about education, your school, and the roles each participant ought to take. Create and conduct activities to bridge any differences that you might discover from the surveys.

1. Go to “The Official Blog of the United States Department of Education” at https://blog.ed.gov/2010/10/parents-and-teachers-what-does-an-effective-partnership-look-like/ and read what parents and teachers say about the role of education. Do you notice any recurring themes within and across the two groups?

2. Read the article “Parent-Teacher Partnerships: A Theoretical Approach for Teachers” at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED470883.pdf We recommend you especially focus on the following sections:

a. The degree of match between teachers’ and parents’ cultural values

b. Societal forces at work on families and schools

c. How parents and teachers view their roles

d. Teachers’ and parents’ role construction

e. Teachers’ and parents’ efficacy beliefs

3. Take notes. What did you find? How does this match with your own understandings and beliefs? What could be some possible areas or sources of misunderstanding?

4. Survey your families and see what they think about education (and your school as an institution). Refer to other surveys we have included in our modules, or check out Harvard’s survey monkey “Parent Survey for K-12 Schools” at http://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/harvard-education-surveys/ You can use this lengthy survey as is, learn from it and modify it to better fit the needs of your school, or create your own from scratch at www.surveymonkey.com. You can administer this survey on paper, online, or both, depending on parents’ and families’ accessibility to the Internet. To ensure a good response rate, you might want to include the survey as part of your Open House activities or as a link in a classroom or school newsletter. Use the feedback from the survey to dialogue with all school community members to bridge the gap between teachers’ and families’ understandings and expectations of education.

InTASC Model Core Teaching Standards

Standard #1: Learner Development

1(c) The teacher collaborates with families, communities, colleagues, and other professionals to promote learner growth and development.

1(k) The teacher values the input and contributions of families, colleagues, and other professionals in understanding and supporting each learner’s development.

Standard #2: Learning Differences

2(d) The teacher brings multiple perspectives to the discussion of content, including attention to learners’ personal, family, and community experiences and cultural norms, including Native Hawaiian history and culture.

2(k) The teacher knows how to access information about the values of diverse cultures and communities and how to incorporate learners’ experiences, cultures, and community resources into instruction.

Standard #3: Learning Environments

3(a) The teacher collaborates with learners, families, and colleagues to build a safe, positive learning climate of openness, mutual respect, support, and inquiry.

3(n) The teacher is committed to working with learners, colleagues, families, and communities to establish positive and supportive learning environments.

Standard #9: Professional Learning and Ethical Practice

9(m) The teacher is committed to deepening understanding of his/her own frames of reference (e.g., culture, gender, language, abilities, ways of knowing), the potential biases in these frames, and their impact on expectations for and relationships with learners and their families.

Standard #10: Leadership and Collaboration

10(c) The teacher engages collaboratively in the school-wide effort to build a shared vision and supportive culture, identify common goals, and monitor and evaluate progress toward those goals.

10(d) The teacher works collaboratively with learners and their families to establish mutual expectations and ongoing communication to support learner development and achievement.

10(m) The teacher understands that alignment of family, school, and community spheres of influence enhances student learning and that discontinuity in these spheres of influence interferes with learning.

1. “The Official Blog of the United States Department of Education” at https://blog.ed.gov/2010/10/parents-and-teachers-what-does-an-effective-partnership-look-like/

2. “Parent-Teacher Partnerships: A Theoretical Approach for Teachers” article at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED470883.pdf

3. “Parent Survey for K-12 Schools” (Harvard’s survey monkey) at http://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/harvard-education-surveys/

4. Family partnerships with high school: The parents’ perspective. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED428148.pdf

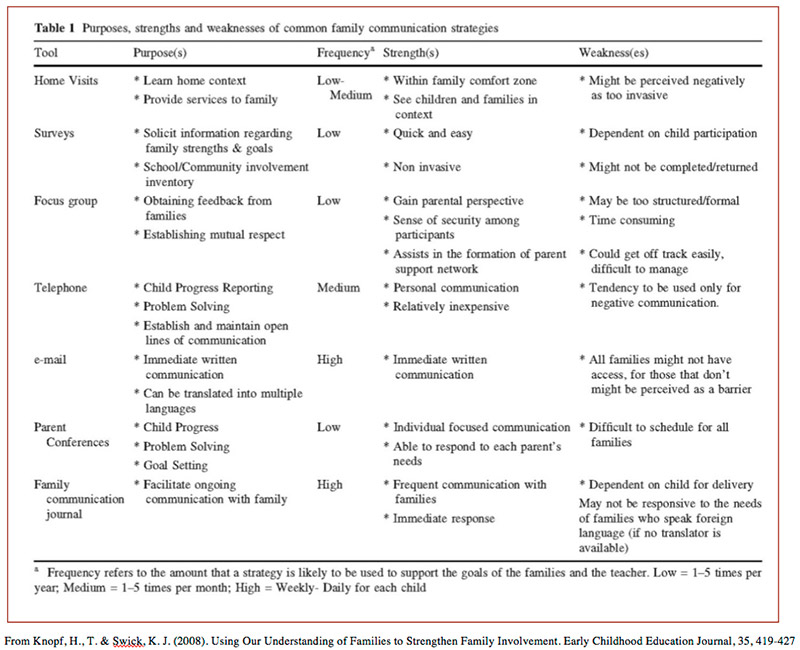

Identify and address gaps in teacher-family communication.

Share with families your expectations about teacher-family communication, gather their input about communication, and use various strategies to align your views with those of families to ensure effective communication with them.

1. What gaps in communication do you think exist between you and your students’ families? How do you think you could overcome them? Using Table 1 below, complete the chart:

| Communication tool | Check if you’ve done it | If you’ve used/done it, how did it go? What went well? What could be improved? | If you haven’t tried it, why not? What’s holding you back from trying it? |

| 1. home visits | |||

| 2. surveys | |||

| 3. focus groups | |||

| 4. telephone | |||

| 5. email | |||

| 6. parent conferences | |||

| 7. family communication journal |

2. What are other communication tools you have used to link family and school? How often have you done them? How did they work for you?

3. What are some other communication tools you have learned about from this module that you would like to implement at your school? What kind of structure or support needs to be set up? Talk to your colleagues, administration, and families. Put your plan into action and evaluate its impact.

InTASC Model Core Teaching Standards

Standard #1: Learner Development

1(k) The teacher values the input and contributions of families, colleagues, and other professionals in understanding and supporting each learner’s development.

Standard #3: Learning Environments

3(a) The teacher collaborates with learners, families, and colleagues to build a safe, positive learning climate of openness, mutual respect, support, and inquiry.

3(f) The teacher communicates verbally and nonverbally in ways that demonstrate respect for and responsiveness to the cultural backgrounds and differing perspectives learners bring to the learning environment.

3(n) The teacher is committed to working with learners, colleagues, families, and communities to establish positive and supportive learning environments.

3(q) The teacher seeks to foster respectful communication among all members of the learning community.

Standard #8: Instructional Strategies

8(q) The teacher values the variety of ways people communicate and encourages learners to develop and use multiple forms of communication.

Standard #10: Leadership and Collaboration

10(d) The teacher works collaboratively with learners and their families to establish mutual expectations and ongoing communication to support learner development and achievement.

10(m) The teacher understands that alignment of family, school, and community spheres of influence enhances student learning and that discontinuity in these spheres of influence interferes with learning.

1. “Beyond the Parent-Teacher Conference: Diverse Patterns of Home-School Communication” at https://archive.globalfrp.org/publications-resources/browse-our-publications/beyond-the-parent-teacher-conference-diverse-patterns-of-home-school-communication

2. “The Teacher’s Role in Home/School Communication: Everybody Wins” at http://www.ldonline.org/article/28021/

3. “Building Trust With Schools and Diverse Families: A Foundation for Lasting Partnerships” at http://www.ldonline.org/article/21522/

4. “Policies & Practices: Family Communications–Ideas That Really Work” at http://www.scholastic.com/teachers/article/policies-practices-family-communications-ideas-really-work

Expand your knowledge of the cultures represented in your classroom and cultivate your cultural sensitivity

Continue your learning as an educator by getting to know more deeply the cultures of your students. Through that process become more aware and sensitive to their backgrounds and needs.

In this activity the purpose is for you to learn about the cultures represented in your classroom and how can you respect and build upon the cultural capital that all participants, including you, bring to the classroom and the learning experience.

1. Read aloud a storybook with themes of diversity or cultural awareness (see book suggestions in Module 1). While engaging students in the reading of the story, have them share their cultural backgrounds. Where in Hawai’i are they from? Or what country or state do they come from? What languages do their family members speak?

2. Have a discussion about where people come from, the languages they speak, and the way they look. Ask students what they think about the differences among these characteristics. Are some characteristics more useful in different environments? Why? Be careful to moderate the discussion so students do not engage in racial stereotyping.

3. Create a survey with the students:

a. Brainstorm with them areas of interest that they have about each other (e.g. where they come from, the language they speak, etc.). Make a list on the board. Be careful of any sensitive topics.

b. Model and show students how these ideas could be changed into a survey. Make a sample survey sheet with questions on the board.

c. Survey the students using these questions. Involve students and have them take turns asking the questions. Demonstrate how they should record their answers (e.g., with tally marks).

d. Transfer the survey “sheet” onto poster or butcher paper. Hang it on the classroom wall as an example survey and as a representation of the diversity of the class.

4. In the next lesson, review the survey results from last lesson. Group students into teams to go to other classrooms to administer the survey. The will learn about the cultural diversity of the grade level/school. (Make sure you communicate with your colleagues ahead of time and make all necessary arrangements so as not to disrupt other classes.)

5. Have students share their findings by teams. Use poster/butcher paper to consolidate the findings. Have a follow up discussion about what this rich diversity means to the students, and what students and teachers could do to welcome and build upon these strengths.

6. Transfer the survey data onto a visual representation (i.e. a graph). Display on your classroom wall and/or, with permission of the school’s administration, on the school wall. Share and discuss these findings in staff meetings with colleagues, Open Houses with families, or via your classroom newsletter.

InTASC Model Core Teaching Standards

Standard #2: Learning Differences

2(d) The teacher brings multiple perspectives to the discussion of content, including attention to learners’ personal, family, and community experiences and cultural norms, including Native Hawaiian history and culture.

2(j) The teacher understands that learners bring assets for learning based on their individual experiences, abilities, talents, prior learning, and peer and social group interactions, as well as language, culture, family, and community values.

2(k) The teacher knows how to access information about the values of diverse cultures and communities and how to incorporate learners’ experiences, cultures, and community resources into instruction.

2(m) The teacher respects learners as individuals with differing personal and family backgrounds and various skills, abilities, perspectives, talents, and interests.

2(o) The teacher values diverse languages and dialects and seeks to integrate them into his/her instructional practice to engage students in learning.

Standard #4: Content Knowledge

4(m) The teacher knows how to integrate culturally relevant content to build on learners’ background knowledge.

Standard #7: Planning for Instruction

7(i) The teacher understands learning theory, human development, cultural diversity, and individual differences and how these impact ongoing planning.

7(k) The teacher knows a range of evidence-based instructional strategies, resources, and technological tools and how to use them effectively to plan instruction that meets diverse learning needs.

7(n) The teacher respects learners’ diverse strengths and needs and is committed to using this information to plan effective instruction.

Standard #8: Instructional Strategies

8(k) The teacher knows how to apply a range of developmentally, culturally, and linguistically appropriate instructional strategies to achieve learning goals.

8(p) The teacher is committed to deepening awareness and understanding the strengths and needs of diverse learners when planning and adjusting instruction.

Standard #9: Professional Learning and Ethical Practice

9(e) The teacher reflects on his/her personal biases and accesses resources to deepen his/her own understanding of cultural, ethnic, gender, and learning differences to build stronger relationships and create more relevant learning experiences.

9(h) The teacher knows how to use learner data to analyze practice and differentiate instruction accordingly.

1. Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

2. Gay, G. (2013). Culturally Responsive Teaching Principles, Practices, and Effects. Handbook of Urban Education, 353-372.

Identify institutional racism in your school system.

Identify five ways in which your school system intentionally or unintentionally promotes institutional racism. Through discussion with peers, develop strategies to counter that racism through changing procedures or policies, educating staff, or other approaches.

1. Institutional racism refers to the policies, practices, and ways of talking and doing that create inequalities based on race. Oftentimes this racism is not obvious, premeditated, or orchestrated. This makes institutional racism even harder to identify and overcome.

Here are some examples of institutional racism in US schools:

- Teacher and school staff attitudes to minorities. For example, having lower expectations for non-mainstream students.

- Using testing and other procedures that are biased against minorities. This happens when tracking is done based on high stakes tests

- Segregating students. For instance, pulling out students who are not native speakers of English or mainstream English.

- Allocation of teachers and resources based on race so that minority students do not have access to the same opportunities to learn.

Think of five ways in which your school engages in institutional racism. As noted above, these practices are often invisible and therefore hard to identify. Please go to the resources page to read about various ways in which schools perpetuate racism to start thinking about the practices that happen at your school. List those practices and name them.

2. Think about the invisible historical, contextual, and structural forces that lead to that racism. Write those sources next to each item in your list.

3. What are some possible ways in which you could contest those forces in your classroom and at your school? In which ways could the community be involved to battle institutional racism?

4. Try out one of the strategies listed above in your classroom and reflect upon the results of the strategy you tried. Was it effective in making racism visible and in putting a stop or diminishing it?

InTASC Model Core Teaching Standards

Standard #2: Learning Differences

2(d) The teacher brings multiple perspectives to the discussion of content, including attention to learners’ personal, family, and community experiences and cultural norms, including Native Hawaiian history and culture.

2(m) The teacher respects learners as individuals with differing personal and family backgrounds and various skills, abilities, perspectives, talents, and interests.

2(o) The teacher values diverse languages and dialects and seeks to integrate them into his/her instructional practice to engage students in learning.

Standard #7: Planning for Instruction

7(n) The teacher respects learners’ diverse strengths and needs and is committed to using this information to plan effective instruction.

Standard #8: Instructional Strategies

8(p) The teacher is committed to deepening awareness and understanding the strengths and needs of diverse learners when planning and adjusting instruction.

Standard #9: Professional Learning and Ethical Practice

9(e) The teacher reflects on his/her personal biases and accesses resources to deepen his/her own understanding of cultural, ethnic, gender, and learning differences to build stronger relationships and create more relevant learning experiences.

1. ARTICLES AND ONLINE PAPERS

Brown vs. Board Documentary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jLcac0KIQHo

Caref, C. (2007). Math and NCLB/No Child Left Behind’s High-Stakes Testing has particularly adverse effects on the math teaching and learning of low-income students of color. Retrieved from

http://www.substancenews.net/articles.php?page=454

Daniels, J. (2011). Racism in K-12 Public Schools: Education Series. Retrieved from http://www.racismreview.com/blog/2011/07/12/racism-k-12/

Van Ausdale, D., & Feagin, J. R. (2001). The first R: How children learn race and racism. Rowman & Littlefield. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED471041

Willough, B. (2013) Is my school racist? Retrieved from

http://www.tolerance.org/magazine/number-45-fall-2013/is-my-school-racist

2. BOOKS

Banks, J. A. (2002). Race, knowledge construction, and education in the USA: Lessons from history. Race, ethnicity and education, 5(1), 7-27.

Blau, J. R. (2004). Race in the schools: Perpetuating white dominance?. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Derman-Sparks, L., & Ramsey, P. G. (2011). What if all the kids are white?: Anti-bias multicultural education with young children and families. Teachers College Press.

Feagin, J. (2013). Systemic racism: A theory of oppression. Routledge.

Kozol, J. (2012). Savage inequalities: Children in America’s schools. Random House LLC.

Motha, S. (2014). Race, Empire, and English Language Teaching: Creating Responsible and Ethical Anti-Racist Practice. Teachers College Press.

Pollock, M. (2009). Colormute: Race talk dilemmas in an American school. Princeton University Press.

3. WEB RESOURCES

Community Change, Inc. Educating and Organizing for Racial Equity Since 1968

Visit at http://www.communitychangeinc.org/

Racism no way. Anti-racism education for Australian schools.

Visit at http://www.racismnoway.com.au/