One of the first major milestones in a child’s life is exiting elementary school and, in the United States, entering junior high, middle school, or intermediate school. Junior high school includes 7th, 8th, and 9th grades, middle school includes 6th, 7th, and 8th grades, and intermediate schools can range in grade levels from upper elementary to 8th grade. In Hawai‘i, there are no junior high schools, so students attend either middle or intermediate schools. All of the intermediate schools in Hawai‘i range from 6th-8th grades with the exception of high and intermediate schools that range from 7th-12th grades and one elementary and intermediate school on Hawai‘i Island that includes grades K-9.

So why are there both middle schools and junior high schools? In his article “A Brief History of the Middle School,” Manning (2000) explained that for the majority of the 19th century, there were eight-year elementary schools and four-year high schools. However, educators began realizing that this 8-4 structure was not meeting the educational and developmental needs of younger adolescents. In the early 1900’s, the first junior high schools were developed (the first one was established in Columbus, Ohio in 1909) that included grades 7-9. The concept of middle level education shifted again in the 1950s and 1960s when educators reexamined whether junior high schools were truly meeting the needs of adolescents. Many educators believed (and many still do), for example, that students needed to be taught about areas such as health and development earlier, and that switching to a middle school model could help students receive that support. These conversations resulted in the emergence of middle schools that start in sixth grade, and the middle school movement has continued to grow rapidly since then (Manning, 2000).

The transition from elementary to middle school can be an exciting time for students and their families. Students especially look forward to increased independence, making new friends, and the opportunity to participate in new activities such as clubs and sports. Parents can watch their children continue growing socially and academically and see them experience new changes and milestones.

However, there are also sources of concern for both families and their children as they prepare for the transition to middle school. For example, there are contextual differences between elementary and middle school, such as unfamiliar peers and teachers, as well as new expectations and school rules (Akos, 2002). Additionally, personal changes that take place physically, emotionally, and socially as children enter puberty can magnify other challenges that students experience during this transition (Steinberg, 2011). Parents may also struggle with knowing how to best support their children through these changes and as they experience shifts in friendships and increased stress over school.

This lesson addresses some specific areas of concern for families and students during this important transition, as well as strategies for how school educators and staff can support families and help elementary students successfully transition to middle school.

References

Akos, P. (2002). Student perceptions of the transition from elementary to middle school. Professional School Counseling, 5(5), 339-345.

Manning, M. L. (2000). A brief history of the middle school. Clearing House, 73(4), 192.

Steinberg, L. (2011). Demystifying the adolescent brain.(Report). Educational Leadership, 68(7), 42–45.

Activities

Organizing a middle school visit

One way elementary school teachers and staff can support families and students during this transition is by organizing a visit to the middle or intermediate school. Parents and students may be concerned about being at a new school, and visiting in advance can help alleviate some of their worry. For example, in Akos’ (2000) survey of 5th graders preparing to enter middle school, 22% of the 115 students expressed that they worried about getting lost and not finding their classrooms. Parents may want to have a sense of the school’s climate, such as the enthusiasm of the administrators and teachers, and how the school offers a safe and positive learning environment.

Elementary and middle school teachers can work together to coordinate a “field trip” to the middle and intermediate schools the students will be attending. If possible, the elementary school teachers can also participate in the field trip. Families can tour their upcoming middle school, meet with their child’s prospective teachers, school counselor(s), and principals. Additionally, upcoming middle school students can have the opportunity to practice new skills, such as switching classes, navigating a larger campus, coordinating multiple lunch schedules, and using a locker. Bailey, Giles, and Rogers (2015) found in their investigation of new middle schooler’s concerns that 97 out of 225 students said they were either very or somewhat concerned about using a locker. Having a chance to practice during a school tour could help students feel more confident. Additionally, elementary school teachers can suggest to parents to buy their children a combination lock so they can practice using it over the summer break.

Parents for Public Schools Hawai‘i (PPSHI) offers transition nights for families and school staff. “These events provide an opportunity to discuss important issues around the transition from elementary to middle or intermediate school. The evening includes a PPSHI presentation by a professor of educational psychology on the developmental changes in adolescence” (PPSHI, 2019).

For more information on school tours, transition nights, and middle school resources from PPSHI, visit https://ppshi.org/middle-school-programs/ or contact middle schools directly to organize individual tours.

*Note: During the COVID-19 pandemic, some of the middle school tours may be offered through Zoom. For more information, contact PPSHI by filling out the following form: https://ppshi.org/contact-ppshi/

1. Parents for Public Schools Hawai‘i at https://ppshi.org

- Article from PPSHI “Making the Jump to Middle School” at https://ppshi.org/making-the-jump-to-middle-school/

2. The following toolkit “Middle School Matters: A Guide for Georgia Schools on Middle School Transition” is intended to to help educators, families and students understand the process of transitioning to middle school, assist in developing a plan to help students successfully transitioning to middle school, provide educators with resources to be used both in the classroom and at home, and to help ensure that students transition to middle school with the full support of their family, school, and community. An example of a middle school transition night agenda can be found on page 75. https://mosesmscounselorscorner.weebly.com/uploads/8/1/8/3/81832484/final_middle_school_transition_toolkit.pdf

3. Teachers can provide the following resource to parents which is intended to help them prepare for visiting their child’s future middle school: https://www.greatschools.org/gk/articles/the-school-visit-what-to-look-for-what-to-ask/

4. Another resource on what to look for during a school visit from Verywell Family can be found at https://www.verywellfamily.com/what-to-look-for-when-visiting-a-school-4118324

5. Akos, P. (2002). Student perceptions of the transition from elementary to middle school. Professional School Counseling, 5(5), 339-345.

6. Bailey, G., Giles, R. M., & Rogers, S. E. (2015). An investigation of the concerns of fifth graders transitioning to middle school. Research in Middle Level Education, 38(5), 1-12. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1059740.pdf

Learning new rules and expectations

Another finding identified by Akos (2002) was that students felt concerned about understanding and following new school rules and expectations. Examples included consequences for arriving late to class and turning homework in late, and whether or not 6th graders could participate in all of the school activities and sports.

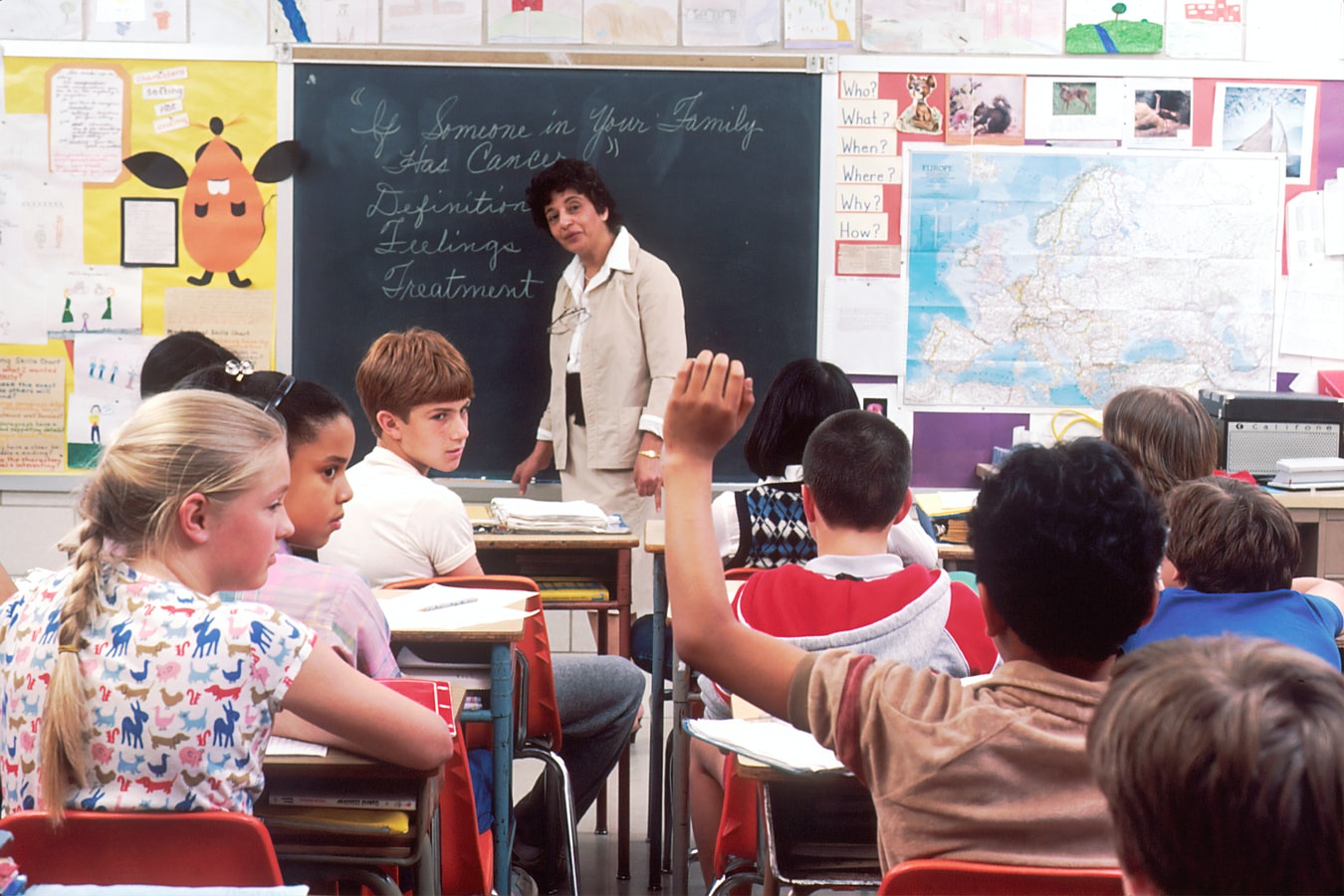

One strategy to address this concern is for middle school teachers and/or administrators to visit elementary classrooms to introduce themselves, explain school rules, and answer student questions. Students may feel more comfortable opening up and asking questions when they are in an environment with which they are already familiar. Including students in creating classroom rules can help students feel valued and part of the community (George Lucas Educational Foundation, 2011). A visiting teacher or administrator can give some examples of how those rules are collaboratively created. The middle school teacher or administrator could distribute student handbooks that the students can take home and show their families. Parents could also be invited into the classroom on this day.

Another strategy is to ask older middle school students to share rules, expectations, and tips that they think are especially important to know with incoming students. The older students could share their experiences during the middle school tour (as discussed above) or perhaps during the first week of school as the new students are settling in.

Additionally, middle schools can provide parents with resources to help them talk with their children about the school rules and understand what is expected. Examples of resources might include the school’s student handbook, pamphlets or bulletins, and website.

1. Akos, P. (2002). Student perceptions of the transition from elementary to middle school. Professional School Counseling, 5(5), 339-345.

2. Bailey, G., Giles, R. M., & Rogers, S. E. (2015). An investigation of the concerns of fifth graders transitioning to middle school. Research in Middle Level Education, 38(5), 1-12. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1059740.pdf

3. George Lucas Educational Foundation. (2011). 10 tips for classroom management: How to improve student engagement and build a positive climate for learning and discipline. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED539390.pdf

Interacting with older students

As incoming middle schoolers enter a new school environment with new and older peers, one area of concern for younger students may be fears of bullying by older students. For example, Bailey, Giles, and Rogers (2015) found in their survey of 225 fifth graders that almost half rated being bullied by older students as one of their highest areas of apprehension. Similarly, Akos (2002) found that 24% of the new sixth graders he surveyed reported specific concerns about being bullied by older students, such as being picked on while riding the bus.

It is important for schools to talk with students about what bullying is, what to do if they are being bullied, and the effects of bystander bullying – seeing someone being bullied and not doing anything about it is just as harmful. Intentionally explaining to students what bullying looks like and that it is not tolerated can help students further understand the effects of bullying, especially as many students may not have been explicitly talked with about this issue.

One strategy to address this area of concern would be to have older middle schoolers help with school tours for incoming students and their families. Older students could assist with showing families around the school, share some of their favorite aspects of middle school, and discuss things they think are important for incoming sixth graders to know. This would give elementary students a positive first interaction with their future older peers.

Another strategy is to build a peer mentoring system, such as one modeled by these guidelines from the U.S. DOE Mentoring Resource Center (MRC) Building Effective Peer Mentoring Services. Younger students can be paired with older students who will mentor them as they adjust and settle into the new school environment. Additionally, parents could be invited into the classroom to meet their child’s “buddy.” According to the MRC, benefits to mentees include stronger connectedness to the school and prosocial behaviors and attitudes. Positive impacts of such programs for peer mentors include improved interpersonal skills, conflict resolution, and increased empathy.

Schools can provide parents with information on how to talk with their children about bullying, what to do if they think they are being bullied, and what to do if they observe someone else being bullied (known as bystander bullying or bystander syndrome).

For example, the National Education Association’s article “Recognizing the First Signs of Bullying” lists several signs that may indicate their child is being bullied. https://www.nea.org/professional-excellence/student-engagement/tools-tips/recognizing-first-signs-bullying Additional suggested resources for parents and educators are listed below.

1. “Building Effective Peer Mentoring Programs: An Introductory Guide” by the Mentoring Resource Center at https://educationnorthwest.org/sites/default/files/building-effective-peer-mentoring-programs-intro-guide.pdf

2. “Recognizing the First Signs of Bullying” from the National Education Association https://www.nea.org/professional-excellence/student-engagement/tools-tips/recognizing-first-signs-bullying

3. “What Parents Should Know About Bullying” from the Parent Advocacy Coalition for Educational Rights’ (PACER) National Bullying Prevention Center at https://www.pacer.org/bullying/resources/parents/helping-your-child.asp

4. Akos, P. (2002). Student perceptions of the transition from elementary to middle school. Professional School Counseling, 5(5), 339-345.

5. Bailey, G., Giles, R. M., & Rogers, S. E. (2015). An investigation of the concerns of fifth graders transitioning to middle school. Research in Middle Level Education, 38(5), 1-12. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1059740.pdf

Supporting parents as they help their children transition from elementary to middle school

As parents and students begin preparing for the transition to middle school, elementary school teachers and staff can provide tools to help. This section describes some strategies and resources that elementary teachers can provide for parents.

- Consider having a parent night at the elementary school where parents can come ask questions and be given resources about how to best support their children during this transition. Families and school staff can bring food to share, and perhaps parents could have some time to visit with each other. The elementary school could invite middle school teachers from the schools the students will be attending to help answer questions and to share their expertise. Elementary school teachers and staff could consult with middle school teachers ahead of time to plan topics the middle school teachers believe are especially important. Hosting this event at the elementary school could be beneficial because parents would be in an environment they are already familiar with and therefore may feel more comfortable opening up and sharing their concerns and questions. It is also beneficial for families to visit the middle schools.

- One suggested resource for parents is this article from Dr. Marie Hartwell-Walker, who discussed several ways parents can help prepare their children before school starts. Her article can be found at https://psychcentral.com/lib/helping-your-child-transition-from-elementary-to-middle-school/ Ideas include:

- Visit the new school

- Organize a time where their child can meet some of the teachers and the school counselor

- Help their child pick out an outfit for the first day of school. Parents can check out “back-to-school” sales and help their child choose some new clothes without having to spend a lot of money

- Start practicing the new morning routine together well before school starts. Most middle schools begin earlier than elementary school, so going through the new routine can help students be more prepared for the first day of school

- Even just a few days of practice would be helpful!

- Another resource to give parents comes from Cheryl Somers, MA, NCC, and contributor to the “Good Therapy” blog. She suggested several tips to help parents support their child’s successful transition to middle school: https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/tips-for-parents-on-a-successful-transition-to-middle-school-0902155

- Encourage self-advocacy through, for example, having your child talk with their teacher if your child forgets to turn in a homework assignment instead of asking you what to do. Then make sure to follow up with the teacher to make sure your child followed through.

- Allow your child to struggle, such as allowing your child to experience the “natural consequences” of forgetting to prepare for class. Make sure that instead of “rescuing” your child, your child understands the consequences that will hopefully lead to a change in habits.

- Encourage teens to try new things, such as a new sport or hobby. Positive risk-taking can also provide parents an opportunity to acknowledge their children’s effort and encourage their children to try new things. Encourage children to commit to the new activity for a specific period of time to promote responsibility and persistence.

- Maintain strong connection and communication with teens by asking about their day and by spending intentional time together.

- Elementary schools could develop a section of their website that is dedicated to providing resources for parents with children transitioning to middle school. Ideas include:

- “Transition Resources for Parents, Teachers, and Administrators” from Edutopia at https://www.edutopia.org/blog/transition-resources-teachers-matt-davis

- “Transition to Middle School” by Peter Lorain for the National Education Association at https://sites.google.com/a/wgu.edu/tps/cohort-seminar/courses-of-study-cos/documents-for-coss/Transition%20to%20Middle%20School.pdf?attredirects=2&d=1

- Several articles and tips for transitioning to middle school as well as suggested books for upcoming middle schoolers can be found at https://www.scholastic.com/parents/school-success/school-success-guides/making-the-move-to-middle-school.html

- The National PTA podcast “Notes From the Backpack” episode 3: “Middle School: What Every Parent Should Know” with Phyllis Fagell – school counselor, therapist, author and mom of three – at https://www.pta.org/center-for-family-engagement/notes-from-the-backpack/middle-school-what-every-parent-should-know

- “Smoothing Your Child’s Transition to Middle School” at https://www.greatschools.org/gk/articles/smoothing-your-childs-transition-to-middle-school/

Providing space for students to share their concerns

Children undergo several changes as they enter adolescence. As the brain continues developing, adolescents gain more control over their behavior and become more purposeful and organized (Wigfield et al., 2006, as cited by Woolkfolk, 2019). However, the prefrontal cortex is responsible for many of these skills, and this area of the brain is not fully developed until the early twenties.Therefore, adolescents often struggle to avoid risky behaviors and to control their impulses (Blakemore & Robbins, 20102; Woolfolk, 2019). Neurological changes also take place during this period.For example, hormones that impact pubertal maturation cause changes in the circadian cycle (Peper & Dahl, 2013). These changes cause adolescents to need about nine hours of sleep per night. Teenagers tend to function better when they fall asleep later and wake up later. To address this, some school districts have recently been exploring later start times for high school students (Woolfolk, 2019). For example, Kaimuki High School on Oahu has later class start times compared to other high schools on the island.

Engagement in risky behaviors typically increases during adolescence, especially with peers. Impulsivity and behaviors seeking immediate reward are attributed to parts of the brain that develop more slowly during adolescence (Blakemore & Robbins, 2012). Adolescents tend to pursue exciting high-intensity experiences more so than children or adults, which is related to hormonal changes (Forbes & Dahl, 2009). Decision making is impacted by increased emotions as adolescents are more likely to make risky decisions in “emotionally charged” situations than are children and adults. Social influences also affect decision making. In fact, peer approval is very important; adolescents are particularly prone to taking risks while with their peers (Blakemore & Robbins, 2012). This is part of the reason why adolescents are not allowed to drive while their friends are in the car in many U.S. states.

Changes also take place in self-concept development (Woolfolk, 2019). For example, teenagers begin making internal comparisons (for example, comparing their performance among different subjects in school) and external comparisons (their performance compared to the performance of others). These self evaluations contribute to their levels of self-esteem and self-worth (Woolfolk, 2019). Additionally, identity development influences how adolescents perceive themselves. Wigfield, Byrnes, and Eccles (2006) described identity as encompassing our general sense of self, as well as our beliefs, emotions, values, commitments, and attitudes. Adolescents may also begin to consider their ethnic identity, which Phinney (1990, as cited by Phinney et al., 2001) suggested could be thought of as “a subjective sense of belonging to an ethnic group and the feelings and attitudes that accompany this sense of group membership” (p. 136). In Hawai‘i, teenagers from diverse backgrounds may begin a deeper exploration of how they see themselves within their own culture(s), within local/Hawaiian culture, and within the broader western context of the U.S.

Another significant area that is further explored in adolescence is sexuality. As teenagers become older, they further consider their sexual-concept and sexual preferences. Social norms, peer scrutiny, and social interactions with their peers also influence sexual decision making and exploration (Tolman & McClelland, 2011). Sexuality is linked to self-esteem and risk-taking behavior and is also impacted by social context, including the composition of the adolescent’s social group and their rank within the group (Blakemore & Robbins, 2012; Forbes & Dahl, 2009).

As these areas can include sensitive topics, it is important for schools to establish safe spaces for students to share their concerns. It is also important for parents and families to have strategies for how to talk with their teens about sensitive subjects. The following activities suggest some ideas for creating safe spaces at school for teens to share their concerns, as well as ideas for supporting adolescents and their families in talking about these topics at home.

Activity 1: Create counseling/support groups

For in-service teachers: Talk with your school counselor about existing support such as counseling groups for students. For example, groups may be established for students with divorced or divorcing parents, those experiencing grief or loss, and/or those who are questioning their sexual identity. If such groups do not exist, discuss how they may be established. Consider which school staff could facilitate the groups, when and where the groups could meet, and what topics could be discussed.

For pre-service teachers: If you were to create this type of group in your future school, what do you think is important to consider? How else might you work toward establishing these groups? What other types of counseling/support groups could be formed?

Activity 2: Providing resources for parents

Find out what resources your school and/or school’s counseling office provides for parents to talk with their adolescents about these topics, and make them accessible to the families of your students. For example, school resources could be added to your class website or social media page. Teachers can also make parents aware of these resources during parent-teacher conferences and meetings.

One resource on how parents can talk about difficult topics is from Common Sense Media. The author provides conversation guides for parents with children ages 2-6, 7-12, and 13-18. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/blog/how-to-talk-to-kids-about-difficult-subjects

References

Blakemore, S. J. & Robbins, T. W. (2012). Decision-making in the adolescent brain. Nature Neuroscience, 15(9), 1184-1191.

Forbes, E. E. & Dahl, R. E. (2009). Pubertal development and behavior: Hormonal activation of social and motivational tendencies. Brain & Cognition, 72(2010), 66-72.

Peper, J. S. & Dahl, R. E. (2013). The teenage brain: Surging hormones—brain-behavior interactions during puberty. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(2), 134-139.

Phinney, J. S., Romero, I, Nava, M., & Huang, D. (2001). The role of language, parents, and peers in ethnic identity among adolescents in immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescents, 30(2), 135-153.

Tolman, D. L. & McClelland, S. I. (2011). Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, 2000-2009. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 242-255.

Wigfeild, A., Byrnes, J. P., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Development during early and middle adolescence. In P.A. Alexander & P. H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of Educational Psychology (2nd ed., p. 87-113). Mahjah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Woolfolk, A. (2019). Educational Psychology. New York, NY: Pearson Education, Inc.

1. “The Teenage Brain” PBS video https://www.pbs.org/video/frontline-inside-teenage-brain/

2. “The Mysterious Workings of the Adolescent Brain” – a TED talk by Sarah-Jayne Blakemore at https://www.ted.com/talks/sarah_jayne_blakemore_the_mysterious_workings_of_the_adolescent_brain?language=en#t-163503

3. “How to Talk to Kids About Difficult Subjects” at https://www.commonsensemedia.org/blog/how-to-talk-to-kids-about-difficult-subjects